BC Wine: How BC VQA Paved the Way

In worldwide terms the story of British Columbia’s modern wine industry is brief. It was fuelled not only by innovation and experimentation but also by sheer determination. The beginning of the modern era can be traced to 1990. It was then, a year after the signing of an agreement on national standards, that British Columbia Vintner Quality Alliance (BC VQA) came into existence.

That moment proved pivotal. BC’s Vintners Quality Alliance was precisely what the name suggests and it helped to forge a cooperative environment. It offered a framework for growers and wineries in working together and this proved vital to building what is now, a quality driven industry.

Notably, the first judging authority and sensory specialist, Marjorie King, was involved in regular technical committee meetings that collaborated to develop those standards.

“We were really aware that we had no industry—and not much credibility,” says King. “But we knew, in order to earn credibility, we had to govern ourselves by world standards. It was vital to adopt proper names for varieties and wine styles (such as ‘Late Harvest’) as well as designate Geographic Indicators (GIs).”

Later King was instrumental in overseeing the sensory tasting panels that were part of BC VQA. Designed to weed out flawed wines that were all too common, she says the panels benefitted from everyone, including winemakers. “Their expertise made a huge difference,” she recalls.

BC VQA’s role as an appellation system was also key. Styled on the European model of Quality Wines Produced in Specific Regions (QWPSR), the arrival of VQA sent a clear signal. Canada’s wine regions, while still very young, planned to be taken seriously.

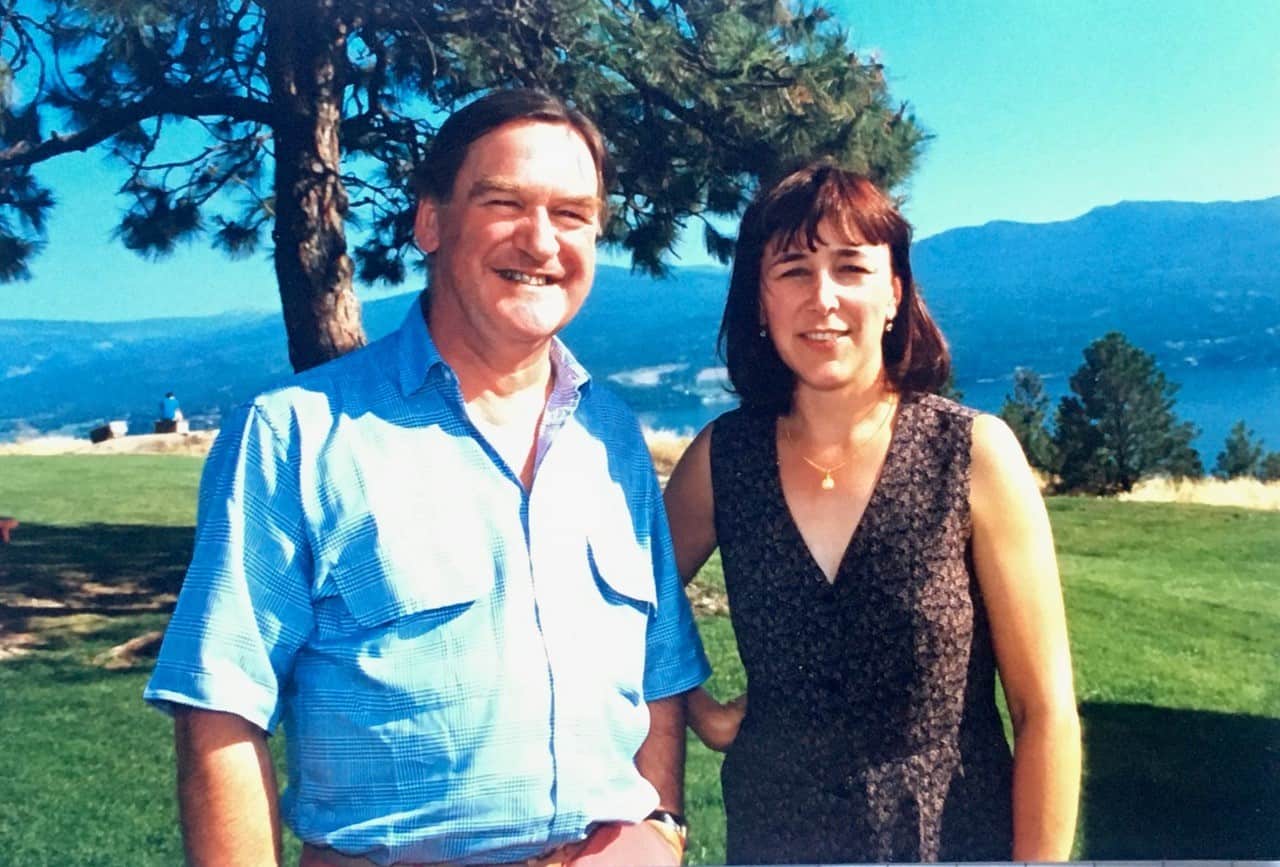

Hugh Johnson with Christine Coletta, inaugural executive director BCWI

Also in 1990, the provincial Ministry of Agriculture established the British Columbia Wine Institute. It was set up to oversee areas of standards, research, marketing and advocacy.

According to Christine Coletta (BCWI’s first executive director) “VQA was incredibly important because we had to galvanize wineries and growers. That coming together with agreed upon standards gave us the critical mass we needed—even if at the time there were only 19 wineries!”

A Challenging Start

Although some major wineries toyed with vinifera, in the 1970s and 80s most of BC’s production was little more than bulk wine of questionable quality. The varieties grown were primarily American hybrids, selected for their ability to produce volume but also for ease of ripening and winter hardiness.

Wineries had to purchase their grapes through the price-controlled BC Grape Marketing Board. It was common practice for growers to turn on their overhead irrigation systems before harvesting, in order to attain the maximum weight possible for their shipments.

Shaped since 1927 by the provincial monopolies, most of Canada’s wine production was controlled by a small but powerful group of processors. They relied mainly on imported juice bottled and sold as ‘Canadian’ product, based on Canadian content regulations that took into account labour and packaging costs.

The consumer was lured by brands that mirrored European products, such as Andres Baby Duck, once Canada’s largest selling wine. Made with Concord grapes, it was a none too subtle nod to the UK’s Babycham, itself a poor ‘Champagne’ knock off.

Against this backdrop British Columbia’s modern day, true home-grown wine industry took its first tentative steps. But it didn’t happen overnight.

Nobody with the hint of a palate would touch BC wine—and most of what passed for Canadian wine was manufactured in industrial plants. Were it not for the efforts of the determined few, little would have changed, at least not on the scale or as quickly as it has.

Most dismissed the BC wine industry or viewed it with disdain— and for good reason. Those early pioneers had an uphill battle convincing a cynical public that anything drinkable would ever come out of BC.

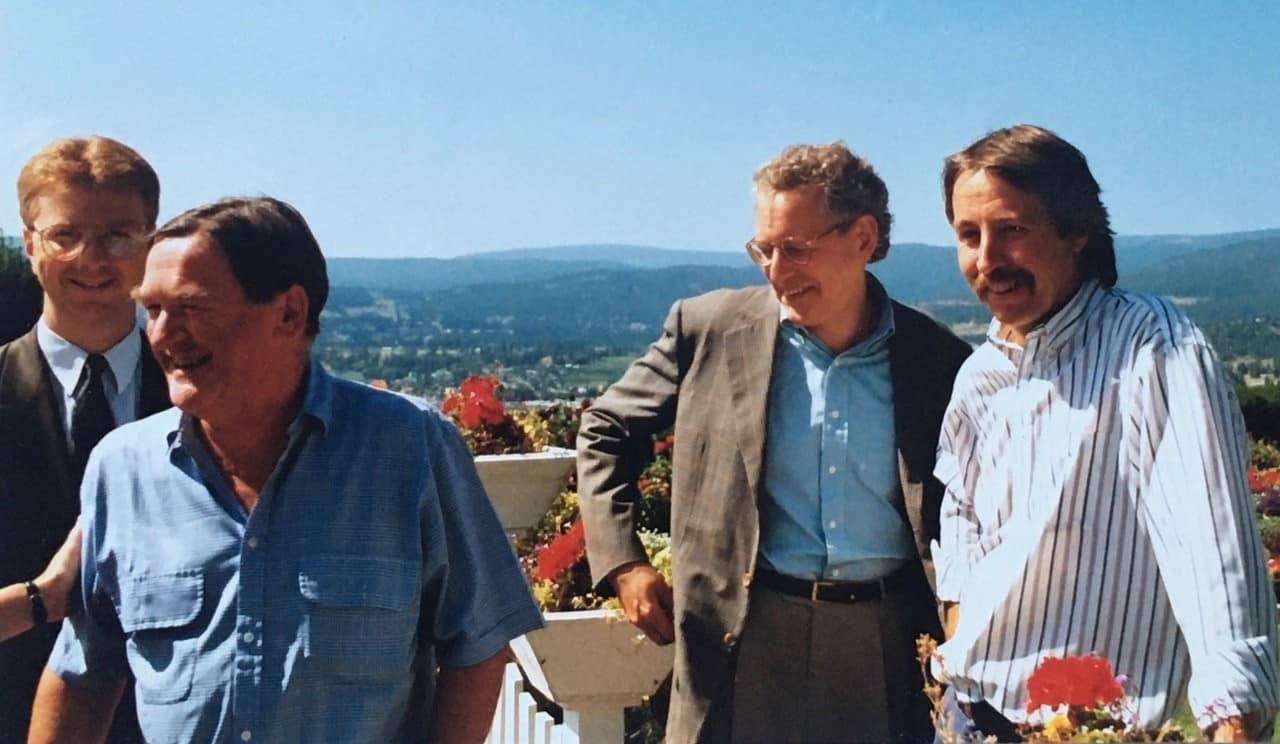

Hugh Johnson (in dashing red pants) after his first Okanagan wine tasting, with the winemakers and winery owners

The Determined Few

At the time the very notion of a regional wine and food culture was too difficult for most Canadians to comprehend. Perhaps it’s not surprising that early efforts

to establish a home-grown, vinifera wine industry came mainly from recent immigrants. Joe Busnardo, who hailed from Italy’s Veneto, had long been convinced that the vinifera of his homeland could grow in the Okanagan.

In 1967 Busnardo purchased land south of Oliver to plant his Divino vineyard (today’s Hester Creek). However, nobody could understand why he would want to grow ‘risky’, low yielding varieties when American hybrids could produce three to four times the volume of vinifera, worth $120 per ton with multi-year contracts.

The authorities refused his request to import 10,000 cuttings, instead allowing just two each of the 26 vinifera varieties requested. Even then, most of these died in quarantine and others were wiped out by frost but Busnardo pressed on. It took him another ten years to get his winery established. Today he continues to grow grapes at Divino Estate Winery on Vancouver Island.

Further north, in 1972 George and Trudy Heiss gave up successful careers in Alberta to plant a vineyard above Okanagan Centre, where Trudy’s father, Hugo Peters, had planted vines a few years prior. Initially they grew hybrids for St. Michelle Wines. But they too desired the grapes with which they had grown up. The couple also lobbied Victoria for the cottage winery guidelines. Drawn up in 1978, they helped to lay the foundation for the land-based wineries and farmgates to come.

Hugh Johnson (second from left) with Anthony von Mandl, John Simes (right) and Steve Bolliger(left)

In 1982 the couple opened Gray Monk Estate Winery. It focused on the proven, cool climate Germanic white varieties brought in for the Becker Project, which George Heiss helped to initiate with renowned Geisenheim viticulturist Dr. Helmut Becker. Prior to BC VQA, the Becker Project was the most important undertaking of the early industry, as it confirmed the suitability and potential of several vinifera varieties, including the Gray Monk’s namesake Pinot Gris.

With a background in sales at Casabello Wines, as well as a passion for home winemaking, the late Harry McWatters (BCWI Founding Chair) was without doubt the region’s most driven and vocal apostle. He left the company in 1980, along with business partner Lloyd Schmidt, to establish Sumac Ridge Estate Winery on part of the Summerland Golf Course. It was no easy feat, that required conquering endless financial and bureaucratic hurdles. But the two persevered, lobbying the province to make the changes needed to foster a viable estate wine industry.

There were others, of course, and not all central to the Okanagan. On Vancouver Island, Dennis Zanatta planted grapes in 1970. Today’s Vignetti Zanatta was part of the government funded Cowichan Project. It trialled around 100 varieties, including the now quite widely grown Ortega, as well as Pinot Gris and Pinot Noir. And in the Fraser Valley, Claude and Inge Violet planted the region’s largest vineyard in 1981, prior to opening Domaine de Chaberton in 1991.

Free Trade Changes Everything

The advent of the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) in 1988 put an end to those poor quality bulk wines that had only been able to compete with imports because of subsidies and a government owned retail network. However, transition to Free Trade was not kind to growers, who saw the biggest harvest in history reduced by over 75 per cent in the following year, as hybrids were pulled out in favour of vinifera and total plantings reduced to just 461 hectares. (1)

Most important, says Christine Coletta, “Growers planted what wineries wanted and they were paid for quality not on volume.”

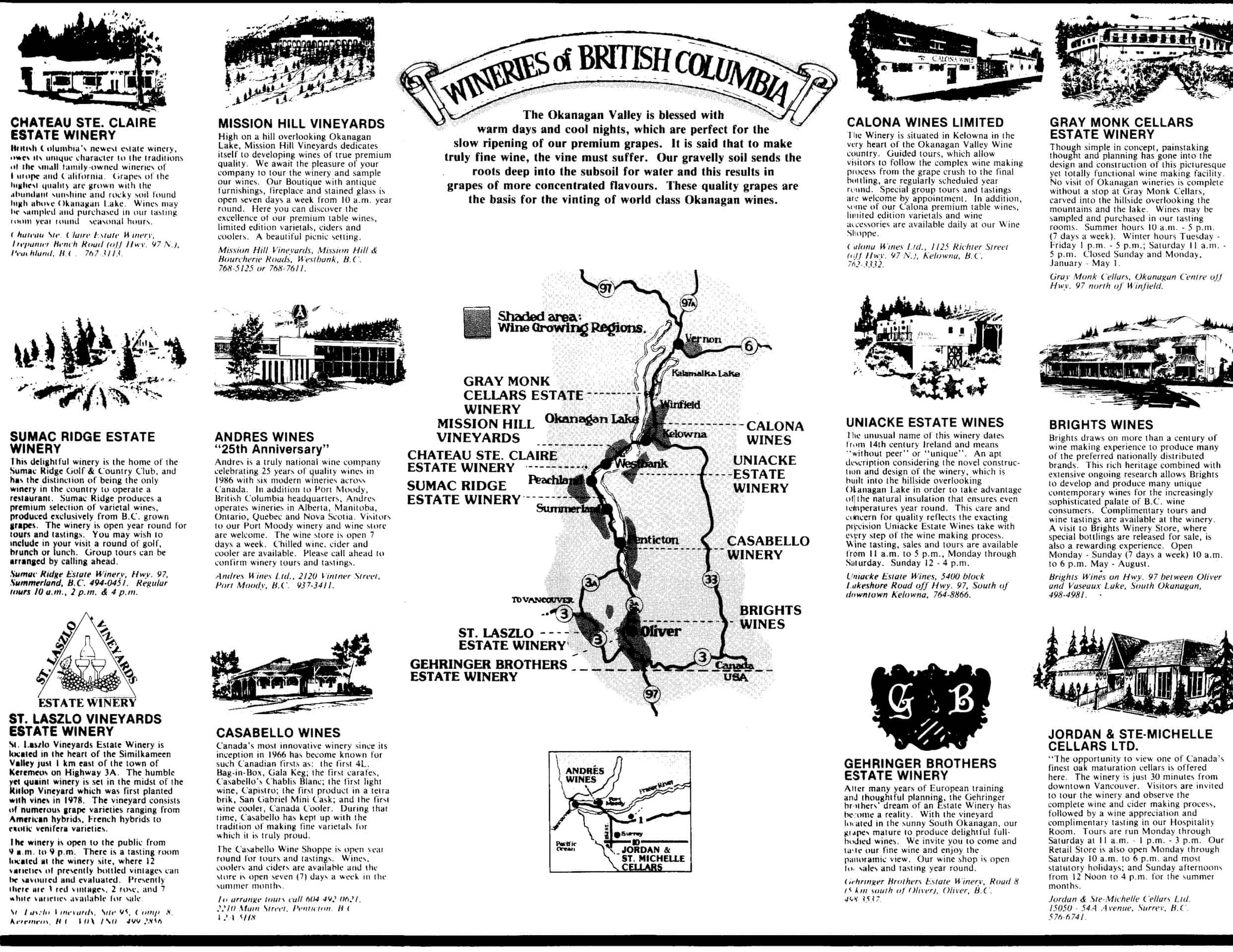

Festival program map detail showing the ten Okanagan Valley wineries (not shown is an inset with Andres in Port Moody)

The ‘90s and Beyond

Thirty years ago there were just 19 licensed grape wineries compared to today’s 282. The area planted has increased ninefold, with 915 vineyards today compared to 115 in 1990. Those early days were marked by bold, often risky ventures. Yet there was a common thread of belief that, given the right conditions and skills, BC—and the Okanagan Valley wine region in particular—could make wines as well as other regions established centuries before.

With standards in place, and growing evidence that the Okanagan could indeed ripen vinifera, the pace picked up. A few more wineries opened and the word was getting out. The core group of land based wineries— including Sumac Ridge, Gray Monk, CedarCreek, Gehringer Brothers and Wild Goose—that helped to lead the region’s drive for quality was ‘100 percent BC VQA.’

In 1992 Mission Hill owner Anthony Von Mandl lured winemaker John Simes to the Okanagan Valley from New Zealand and Montana Vineyards, one of New Zealand’s original wine brands, Simes was the first of many to follow from regions around the world.

Arriving just in time for harvest, Simes immediately implemented a barrel program where there was none, and made a barrel fermented Reserve Chardonnay. Two years later that wine won the coveted Avery’s Trophy in London. It was the first major award of its kind for a BC wines. In fact, the judges were so shocked to discover the winning wine they had chosen came from Canada’s Okanagan Valley (a region of which most had never heard) that they insisted on re-tasting it.

In international terms, it was a defining moment. The Okanagan Valley and BC VQA—had come of age. And the wine world had begun to take notice.

Every licensed winery in the province took part in the 1986 Okanagan Wine Festival

(Multiple sources including The Wines of Canada, John Schreiner)

By Tim Pawsey – Vancouver based Tim Pawsey writes and shoots for numerous publications, including: Where Magazine, Quench, The Alchemist, Vitis, Taste (BC Liquor Stores), Montecristo and others. When not poring over a wine glass or on the business end of a fork he can be found at hiredbelly.com and @hiredbelly / Instagram / Twitter